Reflections on Marcus Aurelius' Meditations

Ancient Rome has always fascinated me. On the one hand, it created the most professional pre-modern military and conquered much of the known world. On the other hand, it embraced and expanded the Greek intellectual tradition. Janus-faced, Rome offered both Caesar and Cicero.

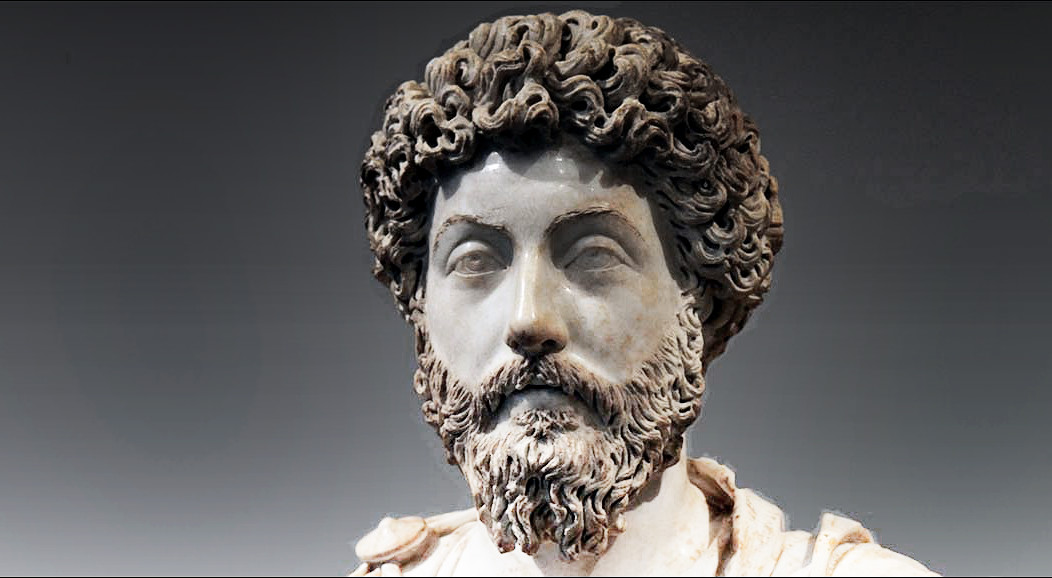

Out of the Emperors, Marcus Aurelius likely best unifies those seemingly disparate aspects of Roman Civilization. Recently I read his Meditations, which are his private writings while serving as Emperor. They are effectively the diary of the most powerful man of the Ancient World, and they focus on his personal morality, his sense of humility based on his self-conception as a mortal relatively insignificant compared to infinite time and space, and his obligation to lead a just life based on the philosophy of the stoics. I found these writings to be quite beautiful and uplifting, and I want to share a few of the key themes.

The Importance of Human Reason

Marcus Aurelius and the Stoics strongly believed in the power of the rational mind. It is the main lever individuals have for living a right and just life. It can be strengthened via education and habit. It is applied through deliberate meditation and journaling. It is focused on answering several crucial life questions.

Who am I? What is my nature?

Despite the celebration of the rational mind, there seems to be an acknowledgement in Marcus Aurelius' Meditations that individual human beings are only partially defined by reason. Much of our nature is emergent outside of the rational mind, from biology or other unconscious forces.

We always have an imperfect understanding of ourselves and our own natures, but the central and most important goal in the stoic view of living a good life is getting to know oneself and using our reason to probe our nature. Having a good conception of ourselves is critical in accounting for our natural tendencies when constructing our moral philosophy. Being aware of our own biases helps empower the rational mind.

This process of self-discovery and the seeking to integrate one's innate nature into the constructs put together by the rational mind seems to be a lifelong quest. We should meditate and journal on this central question of identity each day and use our realizations to evolve our conceptions of ourselves and guide our actions day-to-day.

How do I react to external stimuli that cause me pain?

Man is mortal. We thus suffer injury, illness, pain, and death.

We can't control these external physical and social stimuli, but we can control the way that our rational mind conceptualizes and frames them, which affects our feelings and ability to be happy. Through meditation, we can reconceive and reframe the painful external stimuli in a way that preserves our ability to be happy. In this sort of conception, our sense of reason is a mediator between the external stimuli and our innate nature.

You have power over your mind, not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.

How do I relate to my neighbors, especially those with natures in conflict with my own?

Individuals each have their own innate nature. This leads to different moral philosophies and makes conflict between individuals an essential byproduct of diverse individuals using reason to live their conceptions of a just and good life.

From a Stoic perspective, humans are fundamentally equal (regardless of rank, material wealth, status, etc.) because they possess a similar sense of reason and a common quest to know thyself and pursue a happy and just life.

Because the most critical goal of all individuals is the use of reason to act in accordance with their nature and all individual humans are fundamentally equal in this regard, it is therefore unjust for one mortal to condition or coerce another mortal to act in a manner that runs against their innate nature.

How then to manage inevitable conflict?

From the Stoic perspective, individuals have a moral obligation to find ways to harmoniously co-exist with those whom one finds disagreeable, including collaborating with them to serve wider society. According to Marcus Aurelius, these obligations are not just to kin or tribe, but radiate outwards to concentric rings of family, community, state, and the universal body of all mankind.

Additionally, given that the collective projections of individuals sharing similar natures shape society and politics, the universe is change. The rational mind therefore must continuously re-evaluate, change, and evolve to maintain harmony with the changing times.

How do I resist temptations that seduce the rational mind and betray my personal moral code and innate nature?

The stoics did not just view pain and conflict as a threat to the self, but they also viewed pleasure and praise as potentially threatening as well.

In considering this, it's possibly helpful to conceive of the self as something like a layered cake, with one's innate nature as the foundation, the rational mind in the middle, and one's personal moral code at the top.

In this conception, praise is dangerous because it tempts the rational mind to reorient one's moral code in a manner contrary to one's innate nature. It also causes one to act for the sake of what other people think and not as an outgrowth of the moral code the rational mind constructs from one's innate nature. Doing good for good's sake in accordance with one's moral code and nature is thus positive. Doing good for praise or external reward is negative.

This runs against the philosophical school of thought called utilitarianism that argues that humans have a moral obligation to maximize pleasure and minimize pain, which Marcus Aurelius knew as Hedonism.

The Stoics sought to disarm these temptations by using their rational mind for extreme deconstruction:

How good it is when you have roast meat or suchlike foods before you, to impress on your mind that this is the dead body of a fish, this is the dead body of a bird or pig; and again, that the Falernian wine is the mere juice of grapes, and your purple edged robe simply the hair of a sheep soaked in shell-fish blood!

And in sexual intercourse that it is no more than the friction of a membrane and a spurt of mucus ejected. How good these perceptions are at getting to the heart of the real thing and penetrating through it, so you can see it for what it is!

This should be your practice throughout all your life: when things have such a plausible appearance, show them naked, see their shoddiness, strip away their own boastful account of themselves.

Vanity is the greatest seducer of reason: when you are most convinced that your work is important, that is when you are most under its spell.

Pleasurable things like praise, wealth, sex, fame, and status are exposed as empty when examined by extreme deconstruction. They seduce reason and distract you from the essential goal of living a just and good life according to your innate nature.

How do I relate to the vastness of time and the Cosmos?

As the Roman Emperor, Marcus Aurelius fought the temptations of ego and vanity. He wrote frequently about the uselessness of praise (the "clapping of hands" or the "clapping of tongues") and legacy (how future generations would view him). He fought against these temptations by writing about how fleeting praise is and how the legacy of past men greater than himself was forgotten over the generations.

In particular, he tried to view his individual life in the context of the vastness of space and time. Despite the power of the Roman Empire and his individual authority as Emperor, he conceived that the known world was a drop in the bucket of the immensity of the universe. Furthermore, the Roman civilization was just a blip in the vastness of time.

The Romans had a tradition called the Triumph, where a successful military commander wore a vermillion toga, applied red facepaint, and rode in a chariot as the symbolic representation of Jupiter or Mars. A slave stood behind the victorious general, holding a crown above his head and repeatedly whispering, "Remember you are mortal."

Viewing himself as mortal, small relative to the vastness of time and space, Marcus Aurelius deconstructed himself and achieved a state of detachment. This defanged the temptations of praise or vanity and helped him wield his authority in accordance with his moral philosophy and a detached rational analysis of the problem at hand.

Final Thoughts

Like many, I feel a hunger to find ways to elevate my human spirit and live a happy and just life, and I found many practical lessons in Marcus Aurelius' Meditations. The questions he asks himself are largely universal and timeless, and his use of meditation and journaling as a tool for self-discovery and personal growth remain imminently practical. While his prose can be repetitive at times, the book is short and rewarding.

If you're interested in reading this work yourself, you can download copies for free from Project Gutenberg and purchase inexpensive print and audiobook formats from Amazon.