Missing Prelude to Rust Ownership

Recently, my friend Kait Moreno and I have started a YouTube video series to follow our progress as we go through The Rust Programming Language. If you haven't seen this yet, please consider clicking here to open the playlist of what we've produced so far!

While we initially targeted a weekly cadence, we're recalibrating a bit to give us some breathing room to deal with inevitable life surprises. For example, my lovely wife Erica was recently called and informed that her identity was stolen, after a woman was caught with a fake ID in her name trying to take out a loan. 😬. There's going to be a bunch of neccesary adulting over the next few months getting this sorted, so our Rust cadence will likely slow down a bit. Kait and I want to make sure the new Rust concepts have a chance to sink into our noggins!

In lieu of a weekly video, I've cleaned up some of the notes I've taken while reading around "Chapter 4: Understanding Ownership." While the book does a great job explaining how ownership works in Rust, this post provides a supplementary deeper dive into the heap, the stack, and the shortfalls of garbage collection and C/C++ style manual memory management to better contextualize ownership and illustrate the problems it is trying to solve. If you're coming to systems programming via Rust for the first time, you might find this useful!

Hardware and Addresses

While many developers are familiar with the idea of computer memory (e.g. Why does Chrome take up so much RAM?), when approaching systems programming languages, we need to peel back the abstractions a bit and understand what is happening under the covers. I think a good way to do this is to take a brief look at how memory has changed as computers have evolved.

By giving us a place to store programs, memory is the central thing that makes computers programmable. Back in the 1940s, the first computers were only "programmable" via swappable plugboards. Creating a program required thinking through the logic of the electrical circuits that would accomplish your desired behavior. The layout and position of the connecting wires on the plugboard thus stored the logic of a computer program. Because these boards were so challenging to put together, they were swappable to allow a machine to run different types of programs. Nonetheless, glancing at one of these boards gives spaghetti code a whole new meaning.

Charles Babbage, Alan Turing, and Johnny von Neumann are all early computer scientists that theorized that computers could actually be run by "internal programming," whereby program logic could be encoded as software rather than via physical plugboards. In fact, Ada Lovelace wrote several examples of such programs, making her the first software developer. The problem was that the electrical engineering and materials science lagged the theory, so it took time for computers to catch up.

By the time that computers finally had enough memory to store programs, computer architects needed to figure out a scheme to allow a computer to know where data was stored. The solution was a series of physical addressing schemes, which associate an address with a fixed chunk of data. In a way, you can think of computer memory as a huge array of fixed chunks of data.

This simple physical addressing scheme worked for a while until more sophisticated operating systems added features such as virtualization and timesharing. These new features made security and abstraction more important, leading to the adoption of virtual addressing, where the addresses that programs were aware of differ from the actual physical location of memory in the computer. The operating system translated between this virtual address space and the physical computer hardware.

With some minor changes, this approach of virtual memory effectively continues to this day. When a computer program runs, it requests a contiguous address space of virtual memory from the operating system and copies various data structures to this memory from persistent storage. The program might be spread across different chunks of physical memory and perhaps relocate to high-speed caches on modern processors via a technique called paging, but from the point of view of the program, there is a contiguous block of memory.

How this block of memory is organized is ultimately up to the program, which typically breaks the address space into different sections used for different purposes. Two of the most important of these sections are the call stack and the heap. Traditionally, these areas were adjacent to each other and incremented in opposite directions to avoid spilling over into each other's space (called an overflow).

Stack

The program stack area is a dedicated address space used to store the call stack, a "last in first out" (LIFO) data structure that stores stack frames corresponding to different blocks of scope in the program. Each frame is allocated all at once and thereafter cannot be resized, and it contains control information and fixed-sized variables scoped to that block. The values of these variables can be modified, but because the frame cannot be resized, the data types and collection size are fixed.

Note: If you're unfamiliar with the stack data structure, visualize a stack of papers on a desk. In this stack of papers, shuffling and reordering papers is forbidden. If you write a new paper, you can only add it to the top of the stack (called a push operation). You can also only read the top-most paper on the stack (called a pop operation) before getting to the papers beneath it. Thus the last paper you wrote and added to the stack is the first paper you have to read. This is why a stack is "last in, first out" or LIFO for short.

Let's think about how a call stack works with a concrete example.

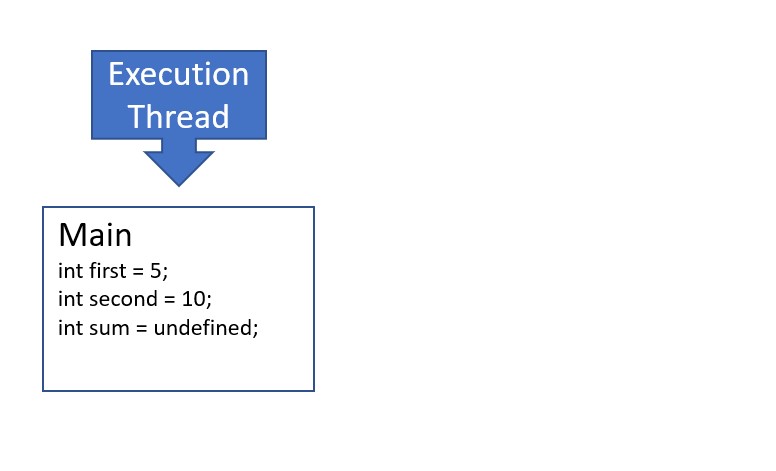

- When we run the binary produced by this C program, the program adds a frame to the stack for the first scope in the program, the

mainfunction, sized to contain all of the variables defined in this scope (the three integers,first,second, andsum). Once allocated, the stack frame cannot grow or shrink.

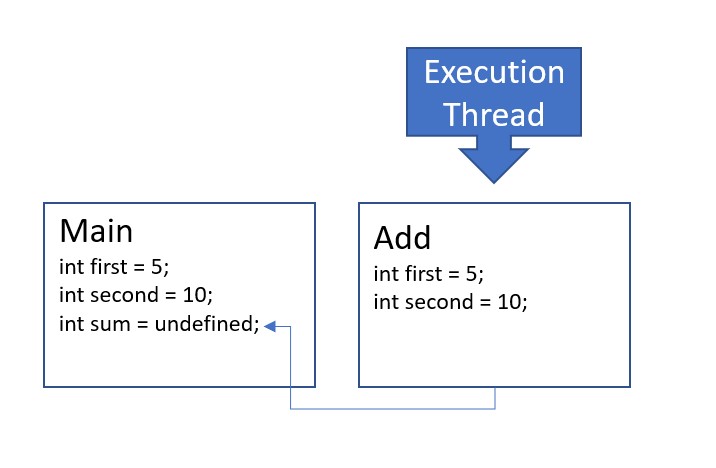

- The main function invokes the

addfunction, causing the execution of the main function to pause until theaddfunction runs to completion. A new frame is added to the stack for the scope associated with theaddfunction call, sized to contain the integersfirstandsecond, which are declared as parameters and whose values are copied from themainfunction's frame.

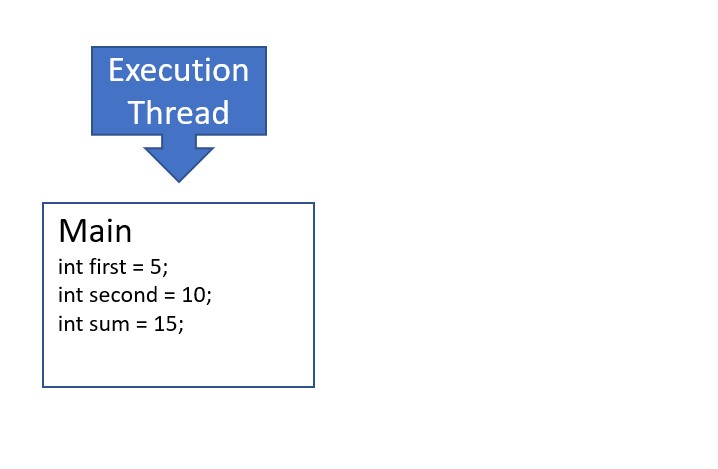

- The

addfunction runs to completion and returns the sum. After the return keyword, the frame for theaddfunction call is popped from the stack, cleaning up associated variables. The frame associated with themainfunction is again at the top of the stack, so execution resumes. The variablesumis updated with the value returned from theaddfunction.

- The

mainfunction prints the result and returns 0. The frame for themainfunction call is popped from the stack, cleaning up the remaining variables. The stack is now empty, terminating the program and passing 0 as a return code to the shell.

The key takeaway is that the call stack uses the stack data structure to store frames containing control information and fixed size variables scoped to particular blocks. When a block invokes a new function, it pushes a new frame to the stack, allocating memory for all static fixed-size variables defined via parameters or within the function's block scope. When blocks run to completion, their associated frames are popped from the stack, cleaning up variables and freeing memory. Because of this automatic cleanup, variables written to the call stack are sometimes called automatic variables.

Despite the limitation that variables on the stack must be preallocated at the start of their associated blocks, a form of dynamic memory allocation is possible via recursive algorithms, whereby a function calls itself until some base case is reached. Though the size of each individual frame is static, the amount of recursion and depth of the call stack varies dynamically.

For example, this Fibonacci program dynamically increases the number of frames (depth) of the call stack to recursively calculate arbitrarily sized Fibonacci series.

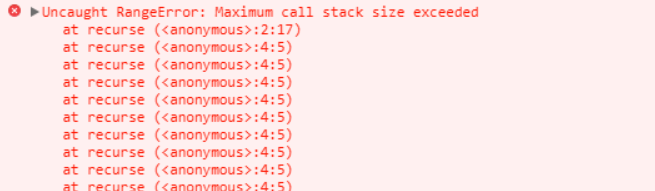

If the base value requires too much work or a programming error causes infinite recursion, there is a danger that the stack might outgrow the size allocated for it and overwrite other values, such as the heap. This is called a stack overflow. Typically, there are safety mechanisms in place, such as a max stack size, so if you have too much recursion, you'll see an error such as "maximum call stack size exceeded."

Heap

The heap is an unstructured address space reserved for dynamic memory allocation and deallocation via memory management APIs. In contrast to the stack, it provides a mechanism for variable-sized data structures and collections. As an array grows, it can allocate a larger space on the heap, copy all data over, and then free up the older smaller data structure. Similarly, strings are effectively arrays of characters under the hood, so effective string manipulation makes heavy use of the heap.

Traditional C/C++ Heap Management

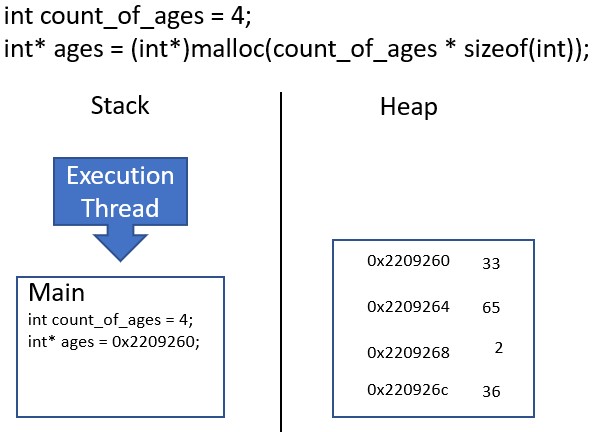

In C/C++, developers directly invoke memory management APIs to allocate and deallocate memory from the heap. Under this model, values are allocated with the malloc command and deallocated with the free command. These values are associated with frames on the stack via pointers: a fixed-size data type that stores the type and memory address of a value on the heap. The pointers live on the stack, but resolve to the value stored on the heap.

In the following simple program, we create an array of integers on the heap to store the ages of an imaginary family. The memory layout of this program is as follows:

To allocate the memory on the heap for this array, we have to do several things:

- Define the capacity of the desired array in a variable

count_of_ages. - Calculate the amount of bytes needed to store this capacity by multiplying the size of an integer by

count_of_ages. - Pass the number of bytes needed to

malloc, which returns a pointer to the allocated memory on the heap. - Cast and store the pointer with the integer data type to enable pointer math.

Once this is complete, we set the value of the elements in the array using indices. Behind the scenes, C uses these indices to calculate a memory offset from the pointer to the first element. This is commonly called "pointer math," which can be unsafe, as we can corrupt data on the heap if we accidentally use an invalid index.

We then use a for loop to print out the value and heap address of each element in the array. To do this, we need count_of_ages to know the outer bounds of our array, as ages only points to the first element.

Finally, we use the free API to deallocate this array. Do you see any problems with the way I'm doing this?

Hopefully this example gives you a bit of appreciation for how the C APIs work. They are extremely low level and leave much to the developer, which makes them powerful yet dangerous. Here are a few of the common sources of bugs:

- Memory Leaks: Living on the stack, pointers are automatic variables that get cleaned up when they go out of scope. However, this lifecycle does not clean up the allocated memory in the heap. If the pointer is lost before being passed to

free, the program loses track of the address on the heap and the memory remains forever allocated. If this happens in a loop in a long-running process, the program will grow and eventually consume all physical memory. - Zombie Pointers: After a developer uses a pointer to call

free, the pointer still contains the address of the now deallocated memory on the heap. If used in an expression, it will resolve to that memory, which can be read from or even written to, corrupting whatever variables are assigned that space on the heap. - Array Decay: When an array is declared, certain meta information about the array seems to live on the stack. This allows use of

sizeof(array) / sizeof(type)to calculate the number of elements in the collection. However, when an array is passed as an argument to another function, size of the array is lost and the array "decays" into a pointer to the collection's first element. To get around this, developers manually create and update an integer containing the size of the array in the same scope where the array is declared. This integer is then passed to functions alongside the array. While this generally works, there are no protections to prevent overflows that accidentally read or write adjacent data in case this integer gets out of sync. - Missing String Null-Terminators: In C, strings are arrays of characters stored on the heap that begin with the address of the first character and terminate with a null character

\0. When strings are resolved, memory is read character by character until a null pointer is found. If this null pointer is accidentally removed, the program will read and interpret subsequest heap addresses as characters. - In parallel programming, multiple threads of execution may have pointers to a single value on the heap, causing a "race condition" where the program might behave erratically when two threads read or write to the same pointer. Getting around this requires advanced knowledge of synchronization constructs.

- Because the manual memory management APIs are a runtime concern, they are difficult to statically analyze. Code might compile cleanly and then crash due to an opaque error called a segmentation fault.

Even if these bugs do not crash the program, they potentially open up security vulnerabilities that allow hackers to read sensitive data or, even worse, inject arbitrary code into the heap. Watch the following video to see how a developer used such an exploit to inject Flappy Bird into Super Mario World:

Managed Languages

For over twenty years, the complexity of these memory management APIs has driven most software development towards managed languages, such as JavaScript, Python, Java, Go, and C#. These languages provide garbage collection that automates the deallocation of memory from the heap. This makes dynamic variables on the heap behave similar to automatic variables on the stack and allows developers to simply allocate variables without ever worrying about cleanup (in theory). For many problem domains, garbage collection increases software velocity by making code quicker and easier to write.

Despite these advantages, there are a handful of downsides to garbage collection:

- It often operates in sweeps, where the execution of the program pauses to allow the heap to be cleaned up. This causes certain aspects of performance to be unpredictable and out of the control of the programmer.

- Depending on the algorithm, it can be foiled by edge cases, such as circular references, leading to memory leaks that fill up the heap over time.

- It is a complex runtime activity that cannot be statically analyzed. This makes it challenging to build tools to troubleshoot memory leaks.

- It enables bad habits leading to inefficient memory utilization and perhaps disincentivizes developers from learning memory-efficient data structures.

To learn more about different garbage collection algorithms, refer to this excellent blog post

Despite the usefulness of garbage collection, there are certain problem domains, such as operating systems and embedded programming, where the disadvantages outlined above are unacceptable. For example, a pacemaker pausing for 100ms of garbage collection could be deadly. For these areas, developers tend to use C or C++ because of their manual memory management APIs.

Rust and Ownership

The core goal of Rust is to find a happy middle ground between traditional C/C++ manual memory management and full-blown garbage collection by extending the natural cleanup of "automatic variables" on the call stack to the deallocation of memory on the heap.

It does this by replacing pointers with ownership as the primary mechanism for associating frames on the stack with values in the heap. Under this model, all memory allocated on the heap is "owned" by one and only one fixed-size variable on the stack. This owner acts as a fixed-size proxy for the allocated data on the heap. Compared to C pointers, owning variables are smarter. They know the starting address, but also the capacity of allocated memory on the heap and the size of the data type or collection written there. This eliminates the problem of array decay.

Finally and most importantly, when a frame is popped from the stack, all variables in the frame that own data on the heap trigger the lifecycle event drop, which deallocates this memory. In this way, the heap inherits the natural cleanup cycle of the stack, making garbage collection unneccesary. By making owning variables and heap allocations share a common lifecycle, most sources of memory leaks and zombie address errors are eliminated.

These advantages come at the cost of a series of compiler rules about how one can resolve memory on the heap:

- Because memory on the heap can only have a single owner, assigning owning variable A to variable B transfers ownership of the allocated memory on the heap from A to B and flags A as inaccessible. This transfer of ownership also occurs when passing an owning variable as an argument to a function.

- Rust References provide a construct similar to pointers in C, but distinct from ownership. This allows us a means to "borrow" a value without changing the ownership relationship, which is useful for function parameters. As with Rust variables, references are immutable by default.

- The Rust compiler prevents race conditions through rules around references. If there are no mutable references, a program can define any number of immutable references to a single owning variable. However, if there is a single mutable reference, there can be no immutable references.

Following these rules requires some adjustment, but it enforces efficient memory management, prevents race conditions, and shifts memory debugging from a runtime concern to a compile-time error.

If you want to learn more about Rust ownership, check out chapter 4 of The Rust Programming Language.