The Io Programming Language

I am not a long-time Io enthusiast. I'm just a polyglot developer backpacking across different language ecosystems with a sense of curiosity and the software equivalent of a Rick Steves' travel guide: Bruce A. Tate’s Seven Languages in Seven Weeks. In previous posts, I introduced my motivations for this project and explored the Ruby and COBOL programming languages.

Our next stop is Io, a little-known scripting language that combines LISP-like homoiconicity (all code is data) with prototype-based objects and a simple message passing model. While largely unsuccessful at gaining mainstream adoption, it demonstrates the power of a well-thought design based on simple constructs. Learning Io is a good way to understand the foundation of prototype-based languages (such as JavaScript) and generally become a better programmer.

If you want to keep track of my travels as I explore other languages such as Prolog, Scala, Erlang, Clojure, and Haskell, follow me on X.

Background

Many programmers hit a point in their career where they feel the itch to unpack the abstractions that they depend on through a passion project. In 2002, Steve Dekorte developed an itch to understand interpreters, and his resulting passion project was the Io programming language. While many programmers would be content to design a toy language to learn the concepts, Steve's appreciation of the theory and history of programming languages allowed him to produce a design that showed great promise and attracted attention. He mixed one-part LISP with one-part Smalltalk and created a tasty syntax that made programming language nerds drool.

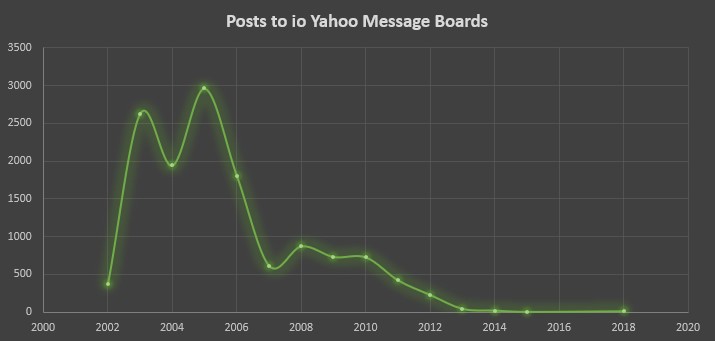

Steve released the first version of Io in April 2002, attracting a community of early-adopters who provided feedback on design and ergonomics and blogged about the language. In 2005, two events caused a spike in interest. First, Steve published an ACM SIGPLAN conference paper explaining his design principles. Second, during an interview at RubyConf 2005, Matz (the creator of Ruby) suggested Io as his top choice of what languages Rubyists should learn in the coming year.

Based on Io message board engagement, the language peaked in 2005 and then gradually declined until 2008, when the famous Rubyist _why blogged about the language.

"Did you know that Io’s introspection and meta tricks put Ruby to serious shame? Where Ruby once schooled Java, Io has now pogoed." ~ _why

The influence of Io on the Ruby community led Bruce A. Tate to include the language in his Seven Languages in Seven Weeks, but he described it as "the most controversial language [he] included," noting that the language was not commercially successful but "has a shot to grow."

In 2014, enthusiasts started to daydream about a 2nd gen Io on the Yahoo message board, but nothing came of it, and the language appears to have effectively flatlined by 2015. A redesign of the Io language website sparked some discussions on Hacker News, including many reminiscences on how developers were impressed by the elegance of the language:

As someone who loves Io, it gets my attention because:

- The language is very mutable, almost all behaviours can be modified.

- It's simple, all you can do is send messages to objects.

- You can write DSLs and macro-like things without special macro support.

- It's so dynamic you'll end up live-coding without realizing it.

- It has less syntax than Smalltalk, it's homoiconic like Lisp, but doesn't need support for macros because of the way messages are handled

A not intolerable way of thinking of Io is it is to object calculus what Lisp is to lambda calculus. There are parts where that analogy breaks down but it's not a bad first approximation." ~smosher

On this thread, Steve mentioned he wanted to do a JavaScript port of Io, but that he was busy with crypto and decentralized web projects. He asked for help with the JavaScript port, but appears to have not gotten a response. If I were in Steve's shoes in 2019, I would consider porting Io to WebAssembly instead. If any readers are interested in this project, consider reaching out to Steve on X.

Why didn't Io catch on?

While this is hard to speculate on, a comment by Steve suggests that Io likely struggled to compete with Lua's performance characteristics as a simple embeddable language for large C or C++ codebases.

"Io and Lua are light and embeddable but while Io is much slower than Go (and much higher level), I suspect Lua is probably the fastest scripting language around and LuaJIT may be competitive (perhaps even faster) than lower level garbage collected systems languages like Go and Java. Looking back, I wish I had written Io in Lua." ~Steve

Another factor is that Steve decided to move onto new projects, such as a WebrRTC-based decentralized message platform in the spirit of Sir Tim Berners-Lee's SOLID project. Had Steve continued to allocate additional time to Io, he might have maintained his community of enthusiasts, but given the recent controversies around social media and data ownership, it's hard to argue with how he's allocating his time.

Easiest way to explore Io

Given the esoteric nature of Io, it should be unsurprising that there aren't any online REPL services supporting this language. I attempted to Dockerize all of the Io tools to make this easier for you, but I unfortunately hit some snags with my Windows Subsystem for Linux setup. In lieu of Docker, I suggest installing the latest official binaries.

These were my steps for installing in my Debian-based environment:

apt-get install wget unzip -y

mkdir ~/temp

wget http://iobin.suspended-chord.info/linux/iobin-linux-x64-deb-current.zip --directory-prefix ~/temp

unzip ~/temp/iobin-linux-x64-deb-current.zip -d ~/temp

dpkg -i ~/temp/IoLanguage-*.deb

Alternatively, if you are on Mac, you can install via Homebrew by running brew install io.

Impressions of the Language

Everything is an Object

The central construct of Io is the object, which provides slots that store either variables or methods.

New objects are created by cloning an existing Object prototype. This adds the prototype in the proto slot.

Vehicle := Object clone

We can then store variables or methods in the object's slots.

Vehicle description := "Something to take you places"

Vehicle drive := method("vroom" print writeln)

In Io, slots act as message receivers, which are registered to handle any messages with the name description or drive. Messages are passed to the object to their left and either return their value or execute the method and return the result of the method. In the above example, print and writeln are messages that are sent to the string "vroom"

Vehicle description // => returns "Something to take you places"

Vehicle drive // => prints "vroom" to the console, returning nil

All slot names can be found via the slotNames method

Vehicle slotNames // => returns list(type, description)

If an object name starts with an uppercase letter, it is a Prototype. If an object starts with a lowercase letter, it is an Instance. Instances are cloned from prototypes and store this prototype in a special type slot. This is somewhat similar to instances sharing a common class in an object-oriented language, but quite a bit looser. Really this is just a convention that helps with certain design patterns.

Car := Vehicle clone

porsche := Car clone

porsche slotNames // => returns list()

porsche type // => returns "Car"

So porsche is an instance of Car, and it has no defined slots. This might not seem useful, but by the power of prototypal inheritance, porsche gets all the behaviors of Car, Vehicle, and Object.

porsche drive // => prints "vroom" to the console, returning nil

Prototypal Inheritance

In addition to normal slots, objects have a slot called Protos, which stores a List (an array) containing all of the prototypes the objects inherit state and behaviors from. Because this is a list, Io supports multiple inheritance, and the "prototypal inheritance chain" is actually not a chain, but a tree.

When an object receives a message, it checks it's local slots for a match. If there isn't one, it triggers a depth first search searching ancestor prototypes for a match. The first match found receives and processes the message. This logic for performing a depth first search lives in the forward method of the base Object prototype.

The simple architecture of message passing and prototypal inheritance is quite powerful. In fact, just about the entire Io language is implemented as methods on prototypes. For example, the base Object prototype stores methods at the slots for and if, so branching and looping works via objects and message passing just like everything else.

This works because the global namespace of Io's execution environment is the Lobby object, which has Object in its prototype chain. The Lobby is the default target for messages when none are explicitly specified, which is how something like the following works:

for(i, 1, 10, write(i, " ")) // => writes "1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10" to the console

Messages and Calls

We've learned that messages are passed to objects and handled by matching slots, and that these slots can exist anywhere in the prototypal inheritance tree. Let's take a closer look at messages themselves.

In fact, when we talk about messages, we are really talking about two things: the message and the call. In the context of mailing a letter, the message is like the letter. It has "Dear John" indicating the name of the person that the message is for and the main content of the message (the arguments). The call is like the envelope. It wraps the message and has an address and a return address to help the postman with delivery.

So a Call has the following slots:

- sender - The object that sent the message

- target - The object that the message is sent to

- message - The message contained in the call

And the message has the following slots:

- name - The slot name that we are trying to match against

- arguments - A List of arguments we intend to pass to a method

Let's illustrate this by a simple example. Imagine that we'd like to instantiate KITT, the famous talking car from Knight Rider. KITT can talk via the method say, but what would the message have to look like for this to work?

kitt := Car clone

kitt say := method(say, say println)

kitt say("What would you like to hear?") // => prints "What would you like to hear?" to the console

kitt drive // => prints "vroom" to the console

The first call we send to KITT matches KITT's local say slot. Inside of the receiving method, the call and the wrapped message can be inspected as follows:

call sender // => "Lobby"

call target // => "kitt"

call message name // => "say"

call message arguments // => List("What would you like to hear?")

The second call we sent to KITT doesn't find a local drive slot, so it traverses the prototypal inheritance chain to the Car Prototype.

call sender: "Lobby"

call target: "kitt"

call message name: "drive"

call message arguments: List()

Given that calls and messages are just normal objects, they provide slots with states and methods. The examples above are just the basics, but the technique provides a powerful tool for message reflection without having to know advanced syntax.

Methods

In Io, methods are anonymous functions that are stored at slots. They are defined by the method method(), which exists as a slot on the base Object prototype. method() takes a variadic number of arguments, where all but the last arguments are arguments to the function you are defining, and the last argument defines the block scope of the method. The last expression of the block is implicitly returned.

In this example, we don't explicitly declare an Object, so it is added as a slot on the Lobby object, which constitutes the global namespace.

add := method(first, second, first + second)

When invoked, a method creates a locals object, which is used to store all local variables. locals has the target of the method as the proto and the value of the self slot. So when we call porsche drive, we are sending a message with the name drive to the target porsche. Even though this delegates up to the Vehicle prototype, in the locals object self is set to porsche.

Concurrency via Actors and Coroutines

Because Io is designed around messages that get passed to receivers, concurrency ends up being quite simple. Prefixing a message with @ returns a future. Prefixing a message with @@ dispatches the message to execute on a separate thread.

Running this

odd := Object clone

odd numbers := method(

1 println

yield

3 println

yield

)

even := Object clone

even numbers := method(

yield

2 println

yield

4 println

)

odd @@numbers

even @@numbers

Coroutine currentCoroutine pause

yields the following:

io coroutine.io

1

2

3

4

Scheduler: nothing left to resume so we are exiting

Net Result: Supreme Hackability

Given that the entire language and standard library is implemented using the same basic concepts as end-user applications, Io is extremely simple to customize and extend. This makes it well suited to metaprogramming and Domain-Specific Languages.

I can do things like implement an XOR type operator using an emoji:

OperatorTable addOperator("🤣", 11)

OperatorTable println

true 🤣 := method(bool, if(bool, false, true))

false 🤣 := method(bool, if(bool, true, false))

true 🤣 true print // => false

true 🤣 false print // => true

Or I can transform JSON containing telephone numbers into Io Maps by making : an operator:

{

"Bob Smith": "5195551212",

"Mary Walsh": "4162223434"

}

// Make the : an operator so we can parse JSON kv-pairs

OperatorTable addAssignOperator(":", "atPutNumber")

// Because atPut already stringifies the key, we string the extra quotes

Map atPutNumber := method(

self atPut(

call evalArgAt(0) asMutable removePrefix("\"") removeSuffix("\""),

call evalArgAt(1)

)

)

// Fires whenever the parser encounters curly brackets

curlyBrackets := method (

writeln("Parsing curly brackets")

r := Map clone

call message arguments foreach(arg,

writeln("An arg: ", arg)

r doMessage(arg)

)

r

)

s := File with("phonebook.json") openForReading contents

// doString evaluates text as Io source code

phoneNumbers := doString(s)

phoneNumbers keys println // => list("Bob Smith", "Mary Walsh")

phoneNumbers values println // => list("5195551212", "4162223434")

Or I can take this further and shadow the forward method used for prototypal inheritance and create a compiler that allows me to define DOM nodes using a LISP like syntax:

Input:

body({"onfocus" : "f(){}", "onredo": "g(){}"},

header(

h1("My Awesome Webpage")

),

ul(

li("Io"),

li("Lua"),

li("JavaScript")

),

list("Io", "Lua", "JavaScript")

)

Output:

<body onfocus="f(){}" onredo="g(){}">

<header>

<h1>content</h1>

</header>

<ul>

<li>content</li>

<li>content</li>

<li>content</li>

</ul>

<ul>

<li>Io</li>

<li>Lua</li>

<li>JavaScript</li>

</ul>

</body>

Compiler:

OperatorTable addAssignOperator( ":", "atPutPair" );

SPACES_PER_INDENT := 4

SGMLBuilder := Object clone

SGMLBuilder indentCount := 0

SGMLBuilder atPutPair := method(k, v,

attribute := Map clone();

attribute atPut( "k", k );

attribute atPut( "v", v );

return(attribute);

);

// curlyBraces is invoked whenever the parser sees { or }

// This converts a json like syntax into an array of tuple-like maps with k,v of SGML attributes

SGMLBuilder curlyBrackets := method(

attributes := list();

call message arguments foreach(attributePair, (

pair := doString(attributePair asString())

attributes append(pair)

));

return attributes;

);

SGMLBuilder indent := method(

write(" " repeated(self indentCount * SPACES_PER_INDENT))

)

SGMLBuilder writeTag := method(

self indent

writeln("<", call sender doMessage(call message argAt(0)), ">")

)

SGMLBuilder openTag := method(tagName, attributes, (

self indent

write("<", call sender doMessage(call message argAt(0)))

if (attributes != nil, (

write(" ")

write(attributes join(" "))

))

writeln(">")

self indentCount = self indentCount + 1

))

SGMLBuilder closeTag := method(

self indentCount = self indentCount - 1

self indent

writeln("</", call sender doMessage(call message argAt(0)), ">")

)

SGMLBuilder writeText := method(

self indent

writeln(call message argAt(0))

)

SGMLBuilder writeList := method(

openTag("ul")

call sender doMessage(call message argAt(0)) foreach(arg, (

openTag("li")

self indent

writeln(arg)

closeTag("li")

))

self indentCount = self indentCount -1

self indent

writeln("</ul>")

)

SGMLBuilder hasAttributes := method(targetMessage, (

targetMessage at(0) asString() findSeq( "curlyBrackets" ) == 0

))

// Object.forward is the mechanism by which Io objects traverse the prototypal inheritance tree.

// It is invoked when a matching slot is not found on the receiving object. I am shadowing this

// in SGMLBuilder to treat missing methods as a value that I wish to template into SGML. This

// is roughly similar to how one can metaprogam using missing_method in Ruby, but it has the

// consequence that SGMLBuilder loses access to the methods on Object.

SGMLBuilder forward := method(

missingMethod := call message name

missingMethodArgs := call message() arguments()

if (self hasAttributes(missingMethodArgs), (

attributes := missingMethodArgs removeFirst();

attributesList := self doMessage(attributes);

attributeStrings := attributesList map(attr, (

key := attr at("k") asMutable removePrefix("\"") removeSuffix("\"");

value := ("\"" .. (attr at("v")) .. "\"");

result := key .. "=" .. value;

result;

))

openTag(missingMethod, attributeStrings)

),

openTag(missingMethod)

)

missingMethodArgs foreach(

arg,

// If this is interpreted as a function, this recursively calls the function on SGMLBuilder,

// which should trigger forward() and template out SGML elements, returning nil.

content := self doMessage(arg);

// If this isn't interpreted as a function, content will be something other than nil,

// and we need to execute the appropriate parser

if (content != nil) then (

if(content type == "Sequence") then (

self writeText(content) // Writes out text inside of SGML Tags

) elseif(content type == "List") then (

self writeList(content) // Given an Io list of strings, generates HTML UL and LI tags

) else (

writeln("Unknown Content: ", content)

)

)

)

closeTag(missingMethod)

)

SGMLBuilder body({"onfocus" : "f(){}", "onredo": "g(){}"},

header(

h1("My Awesome Webpage")

),

ul(

li("Io"),

li("Lua"),

li("JavaScript")

),

list("Io", "Lua", "JavaScript")

)

The source code for these examples can be found in this GitHub repo.

Conclusion

Io is like a 1960s Volkswagen Beetle. It's designed by an enthusiast and optimized to allow other enthusiasts to get under the hood and tinker. This is a breath of fresh air considering many larger languages are like modern luxury cars that can only be serviced by licensed technicians.

Working with Io taught me that a language doesn't need much syntax when the underlying design is strong. Objects and message passing are powerful, and the language is an absolute blast to learn. So while Io has not achieved mainstream success, I think that's fine. It's pleasurable to work with and rewards the programmer with all sorts of insights along the way.

Aside: Do you want to learn how programming languages work?

I've never built a programming language, but I share Steve's interests and have done a bit of research on resources for learning about interpreters and compilers. For those academically-minded, the Dragon book seems to be the dominant academic textbook in the space.

Alternatively, professional programmers might prefer Thorsten Ball's Writing An Interpreter In Go and Writing A Compiler In Go, which offer a paint-by-numbers approach to implementing the Monkey Programming Language.

Finally, for those interested in systems programming languages and associated concepts, such as computer architecture, assembly languages, virtual machines, etc., check out Noam Nisan and Shimon Schocken's The Elements of Computing Systems. It offers a soup-to-nuts instructions that take you from building virtual NAND Gates to writing Tetris in the Jack programming language.

I'm considering these books for future projects and blog posts.